Original publication by Justin McCurry for theguardian.com on 27 June 2022

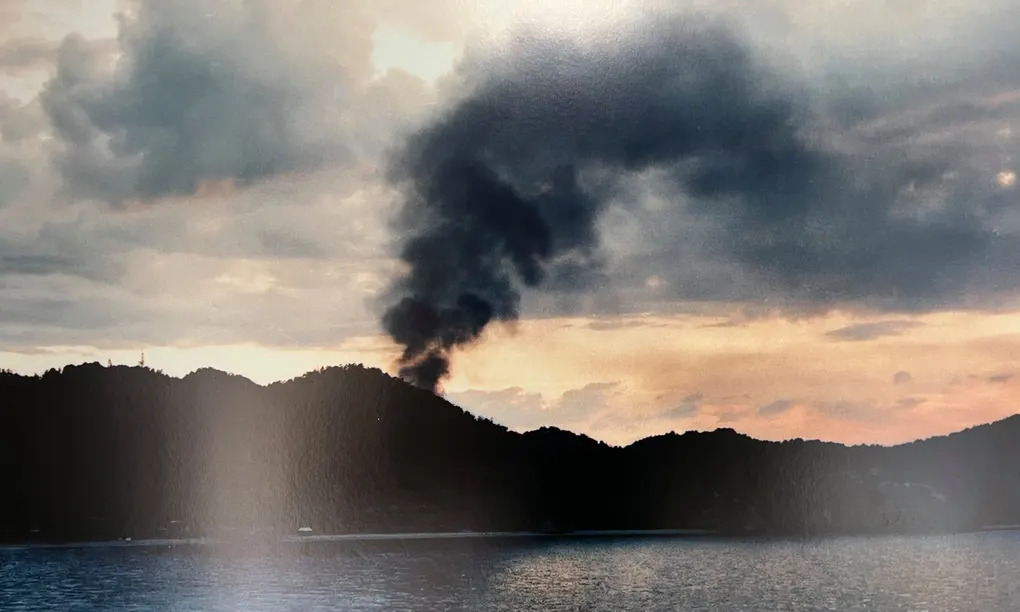

Photograph: Courtesy of Teshima Kokoro no Museum

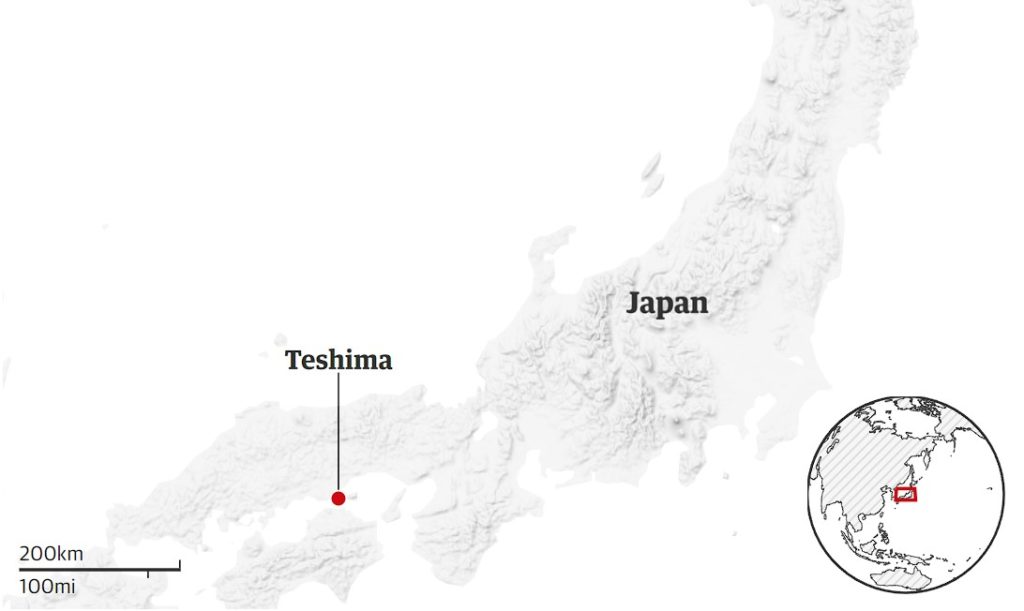

Teshima – site of Japan’s worst case of illegal dumping of industrial waste – was saved by locals who fought relentlessly to have their beloved home restored

Toru Ishii remembers when the shredded car tyres, batteries, and runoff the colour and consistency of treacle blighted the landscape on Teshima, his island home in Japan’s inland sea. Those sights are now confined to a museum, as a reminder of how environmental destruction can unfold in plain sight, and how ordinary people can fight back.

For several years, almost a million tonnes of industrial waste were dumped illegally on Teshima’s western tip, in the worst case of its kind in the country’s history.

The ever-expanding mountain of rubbish earned Teshima the nickname “garbage island”. Its residents wore masks when the waste was burned, sending plumes of acrid smoke into the air. Many complained of sore eyes, and some displayed symptoms associated with asthma. The local fishing and agricultural industries suffered, as consumers avoided Teshima fruit and seafood.

Almost 30 years after residents began their campaign to fight the firm responsible and their politician enablers, the multibillion-yen operation to restore the island to its former state is nearing its end.

Work has begun to remove steel panels that prevented toxic water from leaking into the sea, and by March next year officials are expected to sign off on the cleanup, just as government funds dry up.

Today, Teshima is producing strawberries and olive oil, and is as well known for its art museum, cycling-friendly roads and inclusion in the Setouchi Triennale art festival as for its central role in Japan’s worst case of illegal dumping of industrial waste.

While they celebrate the end of a campaign, islanders are acting to protect the legacy of their once-notorious home – both as a cautionary tale against corporate greed and as an example of the power of civic activism.

“The momentum all came from local people,” says Ishii, a former member of the anti-dumping campaign who now shares his knowledge of the island’s troubled history with visitors. “They funded their own campaign, which meant they could speak freely.”

Photograph: Justin McCurry/The Guardian

A dumping site

In 1975, the misleadingly named Teshima Comprehensive Tourism Development company won approval from Tadao Maekawa, the then governor of Kagawa prefecture – where Teshima is located – to import industrial waste to the island in defiance of the islanders’ wishes.

Aside from pulp, food waste and wood chips, Teshima Tourism started illegally dumped huge quantities of industrial waste – the shredded parts of cars, oil, PCBs and other toxic materials – all with the consent of the prefectural government. As the quantity of waste grew, runoff began seeping into the sea, and Teshima’s reputation as a dumping site was sealed.

When residents complained, Maekawa accused them of being “selfish”. Undeterred, they marched on parliament and held thousands of meetings and events. Campaigners group sat outside the prefectural government offices every day for half a year handing out flyers demanding action against Teshima Tourism and its unrepentant president, Sosuke Matsuura.

In 1990, local police inspected the island, stripped the firm of its operating licence and arrested Matsuura, who was given a token fine and a short suspended prison sentence. The investigation, though, had stirred interest in the media. Sympathetic politicians visited the island, and environmental groups, spurred by successful campaigns against air pollution in the 1970s and 80s, turned their sights on the dangers of industrial waste.

“The attitude in Japan at the time was that pollution of that kind shouldn’t be cleaned up, just buried and hidden from view,” Ishii says.

A remarkable success

In 2000, residents reached a settlement with the prefectural government to clean up the waste. Over the next two decades, 913,000 tonnes were removed and shipped to the nearby island of Naoshima to be treated and incinerated. Work to remove the steel panels began after officials said levels of benzene and other toxic chemicals met national safety standards.

“They ruined the environment and risked people’s health just to make money,” says Ishii, who has turned Matsuura’s old office into a museum dedicated to one of Japan’s most successful environmental movements.

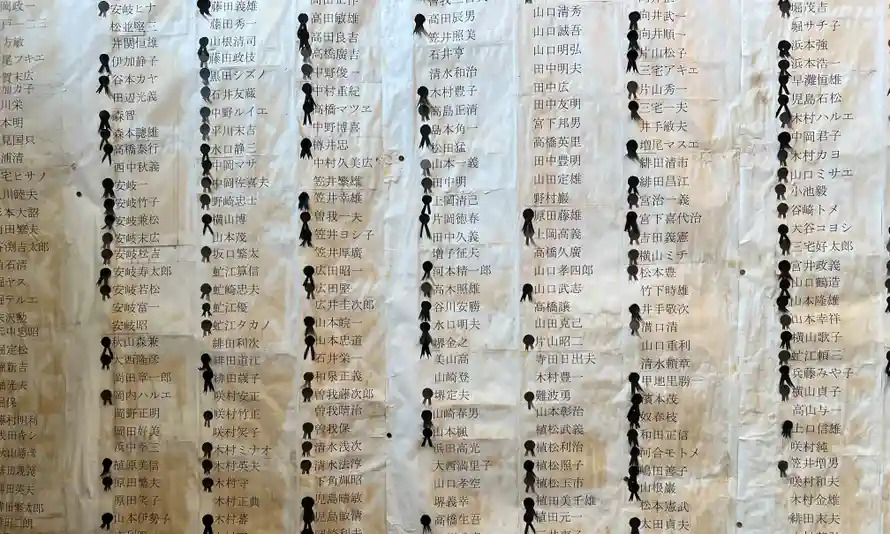

Exhibits include a wall of shredded waste, photographs of demonstrations and a banner that reads: “Give us our island back!” The names of the heads of the 549 households that took part in the campaign cover a wall, with black rosettes pinned next to the 80% who have died. “Every single household demanded action,” Ishii says. “But they understood how slowly things get done in Japan. Few of them thought they would live to see the end of the cleanup.”

The Teshima incident led to the “transformation of waste administration in Japan”, according to Ayako Sekine of Greenpeace Japan, spurring substantial revisions to waste disposal laws, tighter regulations on waste disposal facilities and bigger fines for illegal dumping.

“It is ultimately up to the residents of Teshima to decide what happens next,” Sekine adds. “We expect that the abundant biodiversity will be restored in Teshima and in the Seto inland sea.”

Kiyoteru Tsutsui, a professor of sociology at Stanford University, says the Teshima campaign inspired similar movements in other parts of Japan at a time when the country was only just beginning to appreciate the dangers of industrial waste.

Photograph: Justin McCurry/The Guardian

“I’m not saying everything is perfect in Teshima now, but it has been a remarkable success considering all the damage that was done and the collusion among power holders there,” Tsutsui says.

With a population of just 760, more than half of whom are over 65, the Teshima of today faces new challenges. But there is quiet optimism that its natural beauty and involvement in modern art projects will revive a tourism industry that all but disappeared during the coronavirus pandemic.

While thoughts turn to the future, Ishii, a former farmer, recalls the unlikely band of ecowarriors whose fight is almost at an end. “This,” he says, his eyes fixed on the now-empty dumping site and the pristine ocean beyond, “is their legacy.”