Original publication by Navin Singh Khadka for bbc.com on 3 April 2022

Capturing carbon by increasing forest cover has become central to the fight against climate change. But there’s a problem. Sometimes these forests exist on paper only – because promises have not been kept, or because planted trees have died or even been harvested. A new effort will now be made to track success and failure.

Dr Jurgenne Primavera is being paddled in a canoe along the coast of Iloilo in the Philippines. It’s an idyllic scene but she is frowning. Six years ago these shallow waters were planted with mangroves as part of the country’s ambitious National Greening Programme, but now there is nothing to see but blue water and blue sky.

Ninety per cent of the seedlings died, Dr Primavera says, because the type of mangrove planted was suited to muddy creeks rather than this sandy coastal area. The government preferred it, she suggests, because it is readily available and easy to plant.

“Science was sacrificed for convenience in the planting.”

The National Greening Programme was an attempt to grow 1.5 million hectares of forest and mangroves between 2011 and 2019 but a withering report from the country’s Commission on Audit found that in the first five years 88% of it had failed.

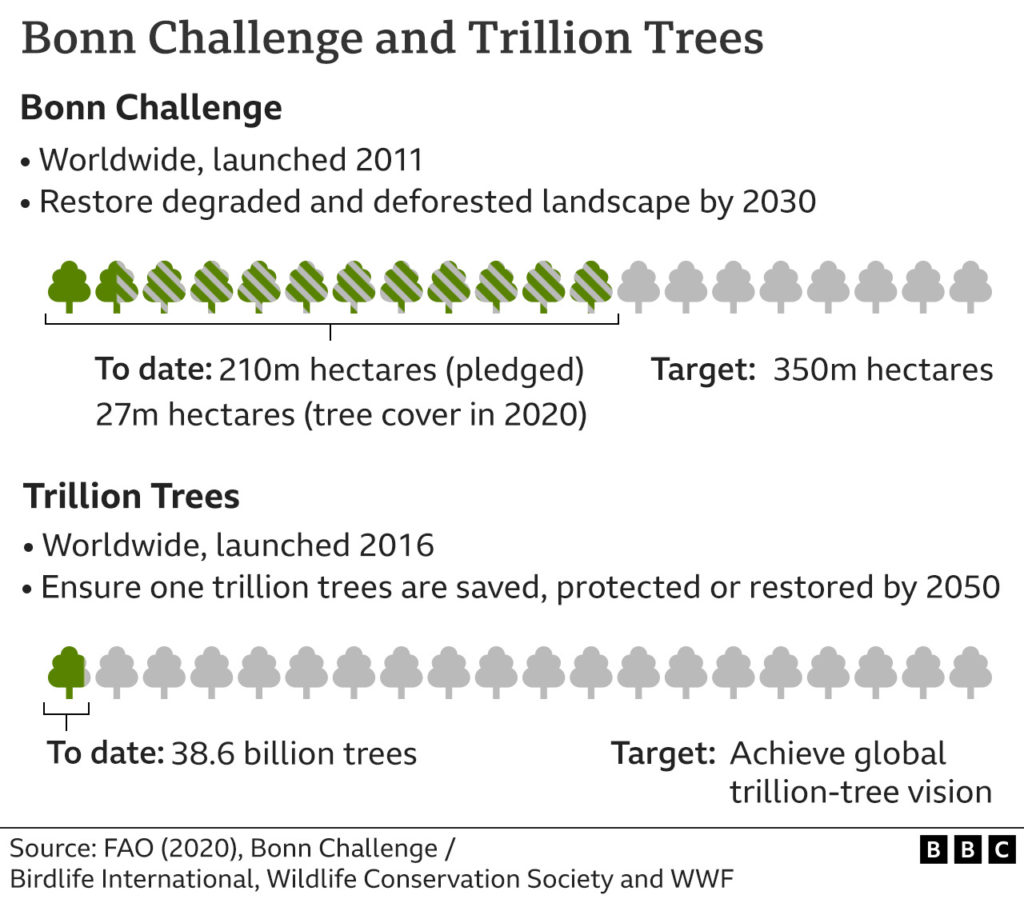

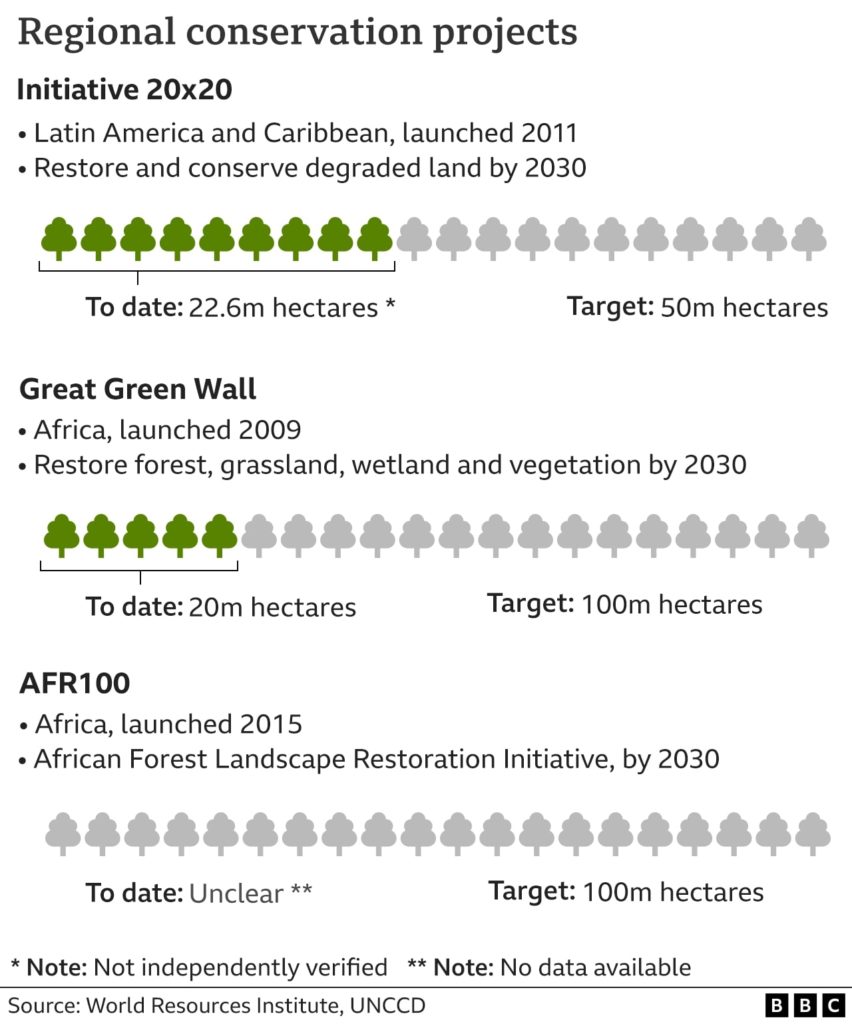

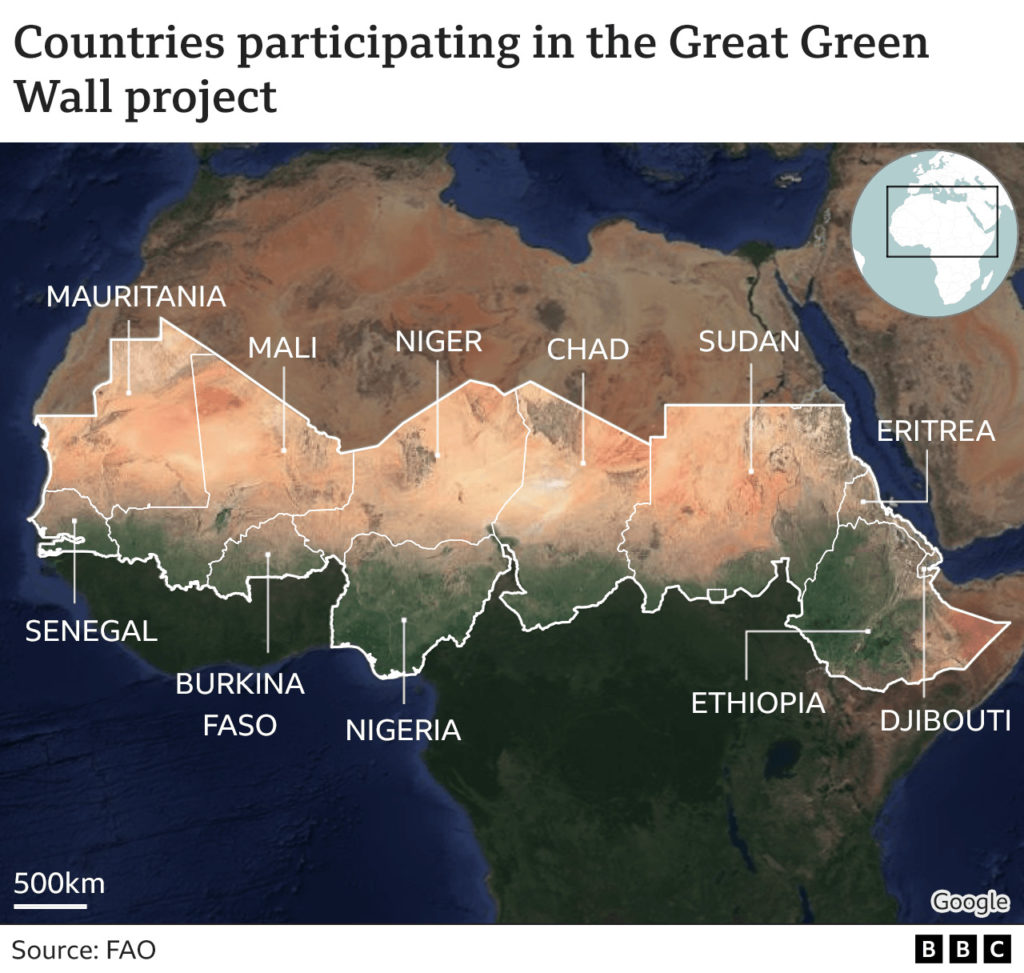

In recent years, many ambitious forest restoration and planting programmes have been launched – some global, some regional – in an attempt to suck carbon out of the atmosphere and limit the rise in global temperatures.

The biggest of them have until 2030 to reach their targets, but they appear to have a long way to go. In some cases it’s simply unknown how much progress has been made.

Tim Christophersen, until this month head of Nature for Climate with the UN Environment Programme, says that of the one billion hectares of landscape that countries have promised to restore worldwide “most” remains a promise rather than a reality.

In some cases, grandiose planting programmes have gone ahead, but have delivered limited results. The BBC has investigated a dozen examples that have flopped – as in the Philippines – usually because insufficient care was taken.

The Philippines government did not respond to requests to comment on the official Commission on Audit assessment that 88% of the National Greening Programme failed.

The local authority that planted what Dr Primavera considers to be the wrong mangrove species for coastal sites disagreed with her, saying that 50% of seedlings had survived in some locations.

In the Philippines at least an audit was published; in many other countries results are unclear.

The Indian State of Uttar Pradesh, for example, has planted tens of millions of saplings in the last five years, but when the BBC went to check new plantations near Banda, it found few alive.

Signs still proudly announced the plantations’ existence, but scrubland plants were taking over.

“These plantations are mostly photo-ops, they look great, the numbers sound stupendous,” says Ashwini Chhatre, an associate professor with Indian School of Business, who has researched ecosystem restoration.

“The current model of plantation requires you to first have nurseries for which you need to procure building materials and then you need to procure sapling bags, barbed wire and other things needed for plantation and then transportation of everything.

“Contracts are awarded for the supply of all these materials, which can also be very leaky. And so many of these people are interested in replanting, they are not interested in the success of plantation.”

Uttar Pradesh’s head of forestry, Mamta Dubey, told the BBC all supplies for state nurseries were purchased through official government channels at competitive rates, and that most plantations had been judged by third parties to be successful.

Prof Ashish Aggarwal of the Indian Institute of Management in Lucknow says India has covered an area the size of Denmark with plantations since the 1990s, but national surveys show forest cover increasing only gradually.

“Even at a survival rate of 50%, we should have seen more than 20 million hectares of trees and forests,” he says. “But that hasn’t happened – the data does not show that addition.”

According to the deputy director of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Tina Vahanen, this problem is widespread, not confined to India.

“Many of the plantations have been promotional events,” she says, “with no follow-up action that is really needed to grow trees.”

The BBC found a different kind of problem in Mozambique, which has allowed private companies to plant large monoculture plantations as part of its contribution to the AFR100 forest landscape restoration initiative.

While many plantations have grown successfully, it’s alleged that in some cases mature natural forest has been felled to make space.

The BBC heard this complaint from villagers in the Lugela, Ile and Namarroi districts in the centre of the country. It is echoed by Vanessa Cabanelas of the NGO, Justica Ambiental, who says that the original landscape worked better as a carbon sink.

“The idea of plantation is sold to us as mitigation for climate change impacts, which is false,” she says.

The companies behind the plantations viewed by the BBC denied that the land had previously been healthy forest. Mozambique Holdings said its rubber plantation near Lugela had been planted on a former tea-growing estate. Portucel, a Portuguese company which has a eucalyptus plantation near Namarroi, said the landscape had been degraded by human interference and that very few remnants of natural forest had remained.

The BBC also witnessed a Portucel eucalyptus plantation being harvested. Vanessa Cabanelas points out that felling trees creates emissions, as does shipping when the logs are exported, and that the dead trees are no longer sequestering carbon. A Portucel spokesman said that new trees would be planted, and the process would begin again.

Portucel has received funding from the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a branch of the World Bank, which has not responded to the BBC’s request for comment.

The Mozambique government has also failed to respond.

It’s against this background that the FAO is this week introducing a new framework for monitoring landscape restoration projects.

National forest monitoring team leader Julian Fox says 20 indicators have been agreed with governments and other partner organisations. These include noting any benefits the forests brings to local communities, as it’s understood that they often fail without local support.

“The idea is to build countries’ capacities to measure and report their progress in a meaningful and transparent way,” he says.

“It’s mainly about making your good monitoring data available to the international community.”

The task of collecting the data still falls to the countries themselves and there is no guarantee they will do it.

But fortunately, this new effort coincides with improvements in satellite monitoring systems, experts say.

“There is a lot of greenwashing around and we have to actively uncover that,” says Tim Christophersen, the outgoing head of UNEP’s Nature for Climate branch.

“There is a temptation for greenwashing, because it costs less than doing the real thing and doing it right.”