Original publication by Isabelle Gerretsen for bbc.com on 19 April 2022

In the midst of the African rainforest, one elusive animal wreaks havoc on vegetation – and in doing so, offers a big favour for the climate.

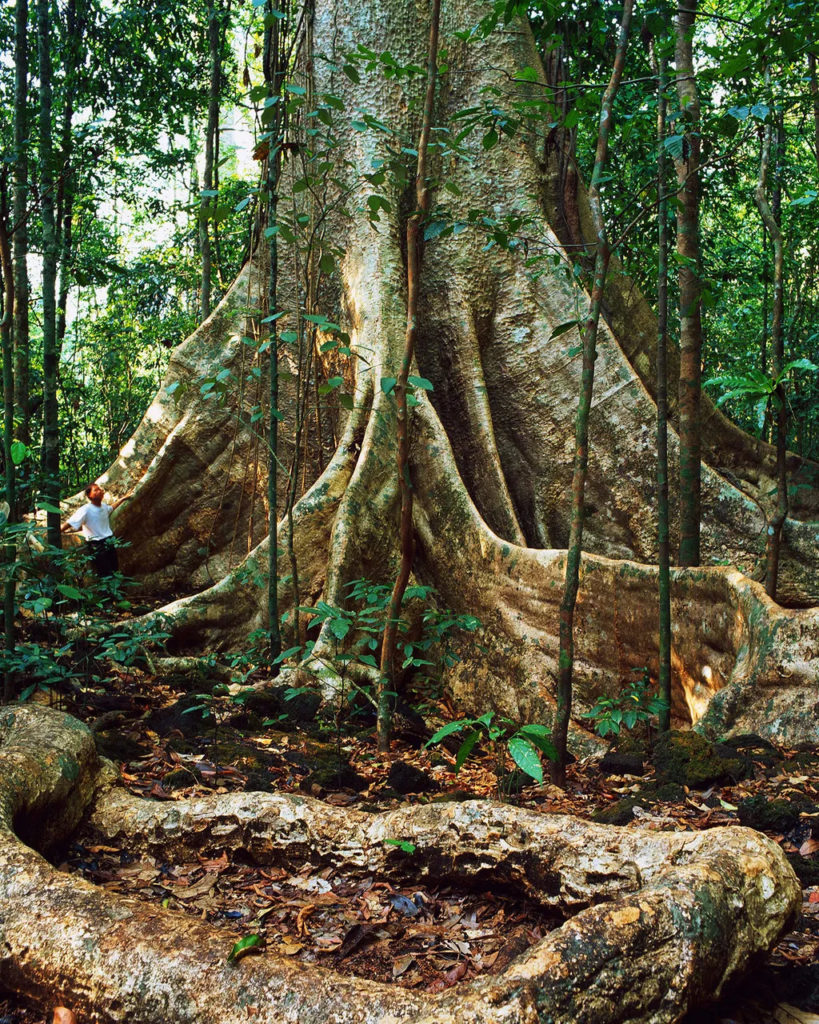

As it trudges through the dense rainforests of West and Central Africa, the forest elephant creates a maze of green corridors by grazing and trampling on small trees in its path. Standing at 3m (almost 10ft), this gentle giant is smaller than its better-known counterpart, the savannah elephant, and remains an elusive, solitary creature. The forest elephant causes mayhem amid the rainforest’s lush vegetation as it strips bark from saplings, digs for roots in the soil and munches on leaves and berries. But this destruction does more good than harm to the forest: it helps forests to store more carbon in their trees and preserves one of the planet’s most vital ecosystems.

Companies and governments around the world are racing to slash their emissions and develop innovative technology to capture carbon. But the African forest elephant is remarkably efficient at storing carbon with no technological aid at all.

African forest elephants are known as “mega-gardeners of the forest”, because of their ability to boost carbon stocks and disperse vital nutrients. A 2019 study found that the elephant’s destructive habits help boost the overall amount of carbon stored in the central African rainforest. Each forest elephant can stimulate a net increase in carbon capture of these rainforests of 9,500 metric tonnes of CO2 per sq km. This is equivalent to emissions from driving 2,047 petrol cars for one year.

Scientists initially carried out fieldwork at two sites in the Congo Basin, one where elephants were active and one where they had disappeared, and recorded the differences in tree cover and wood density. They then built a model that tracked the dynamics of the forest, such as biomass, tree height and carbon stocks, and simulated elephant disturbance by increasing the mortality of smaller plants.

A living elephant provides services worth millions, it is helping us fight climate change and is worth much more alive than dead – Ralph Chami

The model showed that the forest elephants reduced the density of stems in the forest, but increased the average tree diameter and the total biomass above ground. The reason is that the elephants graze and trample on trees smaller than 30cm (1ft) in diameter, which compete with bigger trees for light, water and space. By taking out the competition, the larger trees flourished.

As a result, the larger trees grew even taller thanks to the elephants’ habits, says lead author Fabio Berzaghi, a researcher at the Laboratory of Climate and Environment Sciences in Gif-sur-Yvette, France.

(Credit: Getty Images)

The smaller trees, which elephants prefer to eat, have lower wood density, which is linked to a faster growth rate and higher mortality. The elephants’ behaviour promotes the growth of slower growing trees that store more carbon in their trunks, says Berzaghi. The carbon storage capacity of trees mainly depends on their volume and wood density, although denser wood takes more resources and time to build, he adds.

“You can think of the elephants as forest managers,” he says. They are a “keystone species”, meaning that they play a vital role in maintaining the biodiversity of their habitat.

We’re losing our natural capital and its biodiversity. If we lose that fight, we die too. But if we invest in nature, it will boomerang back to all of us by sequestering carbon – Ralph Chami

Besides eliminating competition, the elephants also disperse seeds and nutrients as they brush past vegetation and distribute poo around the forest, helping trees grow faster, says Berzaghi. “Elephants help disperse trees, which other animals rely on. The trees promoted by elephants support primates and many other animals.”

The extinction of forest elephants would result in a 7% loss of carbon stores, 3 billion tonnes in total, in the central African rainforest, according to the study. That is equivalent to emissions generated by more than 2 billion petrol-powered cars over the course of a year.

“It sends a pretty strong message for the conservation of forest elephants,” says Berzaghi.

There is a very high risk of African forest elephants going extinct. They are critically endangered, with populations shrinking rapidly due to poaching and deforestation. In the 1970s, there were 1.2 million elephants roaming across huge swathes of Africa, but they have been driven to the brink of extinction by poachers and habitat loss. Today just 100,000 remain, according to a 2013 study.

“At least a couple of hundred thousand forest elephants were lost between 2002-2013 to the tune of at least 60 a day, or one every 20 minutes, day and night,” Fiona Maisels, co-author of the study and a scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, said at the time.

“By the time you eat breakfast, another elephant has been slaughtered to produce trinkets for the ivory market,” she said.

“We have lost a large number of forest elephants in the past two decades,” says Thomas Breuer, African forest elephants coordinator at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). “Forest elephants have a much slower reproductive pattern [than savannah elephants], and therefore it takes much longer for populations to recover.”

“Their behaviour has been disturbed by poaching. Many don’t have mothers and can’t learn the individual movement patterns that they normally inherit from the matriarch,” he says.

As their habitat shrinks, elephants are also coming into much closer contact with humans, which has led to an increase in retaliatory killings of elephants, he says.

Climate change is also leading to a decline in fruiting events in African rainforests, leaving elephants highly vulnerable to a reduction in their food supply, according to a 2020 study by Emma Bush from the University of Stirling in Scotland.

Valuing nature

If the herd of African forest elephants returned to its former size and recovered their range of 2.2 million sq km (0.85 million sq miles), they could increase carbon capture by 13 metric tonnes per hectare, according to Berzaghi’s study. This is equivalent to emissions generated by 10 petrol cars over the course of one year per hectare.

Berzaghi says the study shows that survival of forest elephants is critical for preserving the Congo Basin, the world’s second largest rainforest, as a major carbon sink.

(Credit: Getty Images)

This has become even more urgent now that parts of the Amazon rainforest are losing their function as a carbon sink, he says. According to research by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), over a quarter of the Amazon now emits more carbon than it absorbs.

“This is a huge impact, you know directly because we are emitting CO2 to the atmosphere, which is accelerating climate change but also because it is promoting changes in the dry season conditions and stress to trees that will produce even more emissions,” lead author Luciana Gatti told BBC News in July 2021.

“We’re not going to get to carbon neutrality if we don’t invest in nature-based solutions,” Berzaghi says.

In its latest report in February, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlights nature-based solutions as a crucial tool to tackle climate change and draw down carbon emissions from the atmosphere.

“By restoring degraded ecosystems and effectively and equitably conserving 30 to 50% of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean habitats, society can benefit from nature’s capacity to absorb and store carbon,” Hans-Otto Pörtner, one of the co-chairs of the IPCC report, said in a statement.

Ralph Chami, assistant director of the Institute for Capacity Development at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), is on a mission to highlight the value of nature conservation in the fight against climate change. The economist is doing it in a way that may well make politicians and companies take notice: by putting a monetary figure on a forest elephant.

Using the findings from Berzaghi’s 2019 study, Chami valued the carbon capture services of each forest elephant at $1.75m (£1.33m), with the total value of the herd, restored to its former size of 1.2 million, worth an estimated $36bn (£27.5bn). Chami based his calculations on the average market price of a metric tonne of carbon dioxide at the time – just under $25 (£19) in 2019. Poaching would result in $10-14bn (£7-10bn) of lost carbon services, according to recent analysis by Berzaghi and Chami.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Rather than viewing elephant conservation as a cost proposition, we should view it as an investment, he argues.

“The forest elephant is a natural asset that provides value to us over its lifetime,” he says. “A living elephant provides services worth millions, it is helping us fight climate change and is worth much more alive than dead.” The ivory of a dead forest elephant is valued at around $21,000 (£16,000).

“We’re losing our natural capital and its biodiversity. If we lose that fight, we die too,” he says. “But if we invest in nature, it will boomerang back to all of us by sequestering carbon.”

It is not the first time that Chami has put a price on a species. In 2019, he published a report with other IMF economists looking at the climate benefits of protecting whales. The analysis found that, when you add up the value of the carbon sequestered by a whale during its lifetime, the average great whale is worth more than $2m (£1.48m), with the entire global stock amounting to over $1tn (£740bn).

When whales die, they sink to the ocean floor and all the carbon stored in their huge bodies is transferred to the deep sea, where it remains for centuries.

Chami says putting a price on species is the best way to convince countries to protect them. “I wanted to translate those climate benefits into dollars and cents and put the [numbers] in front of policymakers.”

Selling elephants’ carbon services

Others are taking the concept of an elephant’s monetary value a step further. The startup Rebalance Earth aims to use Berzaghi’s scientific findings and Chami’s valuation to sell elephants’ carbon capture potential to companies around the world.

Building on the carbon offsetting market, which enables companies to offset their emissions by paying for tree planting or renewable energy projects elsewhere, Rebalance Earth has started selling ecosystem tokens which represent the carbon captured by each elephant.

“The monetary value of the forest elephant is directly related to how much carbon sequestration they perform within their lifetime and that amount is multiplied to the present price of a carbon offset,” says Rebalance Earth’s chief executive Walid Al Saqqaf.

(Credit: Getty Images)

Companies who buy the tokens are paying to protect the elephants, with funds raised going towards park rangers and local communities, according to Al Saqqaf. The entire transaction will be managed and monitored via private blockchain technology.

“Everyone loves elephants, but does that stop their decline?” he says. “We do not make the right choices based on good intentions, we make decisions around our wallet. How can we use that financial initiative to do the right thing?”

Rebalance Earth is launching a pilot project in Gabon, where up to 70% of Africa’s forest elephants reside. Gabon accounts for almost one-fifth of the Congo Basin forest and has lower deforestation rates than its neighbours, the Republic of Congo and Cameroon. However, forest guards in Gabon threatened to go on strike this year, due to poor working conditions and late pay.

“Our funding will make sure that there are enough rangers to protect the elephants and invest in local communities,” says Al Saqqaf.

Some people are sceptical about Rebalance Earth’s approach, citing environmental and ethical concerns around using digital tokens supported by blockchain to fund conservation.

Catherine Flick, senior researcher in computing and social responsibility at De Montfort University in Leicester, UK, says the main problem is that it is “speculative” and “very hard to regulate”.

However, Al Saqqaf argues that the “beauty” of a blockchain system is that each party has exactly the same access to information as any other. “As our platform expands we will be building an independent governance body and will be reviewing their role to verify transactions,” he adds.

Flick says there is also the issue of who benefits from the programme: the big companies who buy the tokens or the local communities who carry out the conservation work?

Al Saqqaf says park rangers will be paid in their local currency, as will communities during the pilot project. When the initiative is scaled up individuals will be able to spend the tokens in dedicated shops, health and education facilities, he says. Revenue raised by the scheme will be invested in local healthcare and education, he says.

From a climate perspective, there are additional concerns around using blockchain, which can be highly energy-intensive. Rebalance Earth says it will use the private R3 Corda blockchain, which it claims uses roughly the same amount of energy as sending an email. Whereas Bitcoin and other public blockchains use the highly energy-intensive “proof of work” mechanism to verify transactions, R3 Corda is a private blockchain using a validity consensus and uniqueness consensus mechanism, which consumes far less energy as it does not require computational power to solve a mathematical problem.

Breuer says the pilot project is a “fantastic initiative” but identifies several potential pitfalls. “It’s absolutely needed to have a mechanism that puts money towards maintaining forest elephants and increasing local people’s ability to coexist with the wildlife,” he says. “But we need to be honest about the limits and challenges of such a concept.”

For instance, there’s the practical problem of tracking the elephants. “How are you going to know these are the same elephants? They are not easy to identify,” he says.

(Credit: Getty Images)

It is also difficult to convince local communities of the “intangible benefits” of such an initiative, says Breuer. “If you go to a Central African village and tell them about the concept of blockchain, they will say ‘if we kill one elephant, we will have meat for a certain amount of time and that is more valuable to us’,” he says.

Conservation efforts should take place at a grassroots level and focus on helping communities live alongside the elephants, according to Breuer. Funding should also be directed towards the prevention of poaching and enforcement, he says.

“We need to make sure that the money reaches the ground. Solutions are always in the field, not in the capitals,” he says.

The ultimate aim, says Breuer, should be convincing local communities that conservation is a worthwhile pursuit, one that brings jobs and prosperity to the region. “So that within one or two generations, they feel that they cannot live without conservation.”