Original publication by David Danelski for news.ucr.edu on 12 December 2022

An insidious category of carcinogenic pollutants known as “forever chemicals” may not be so permanent after all.

University of California, Riverside, chemical engineering and environmental scientists recently published new methods to chemically break up these harmful substances found in drinking water into smaller compounds that are essentially harmless.

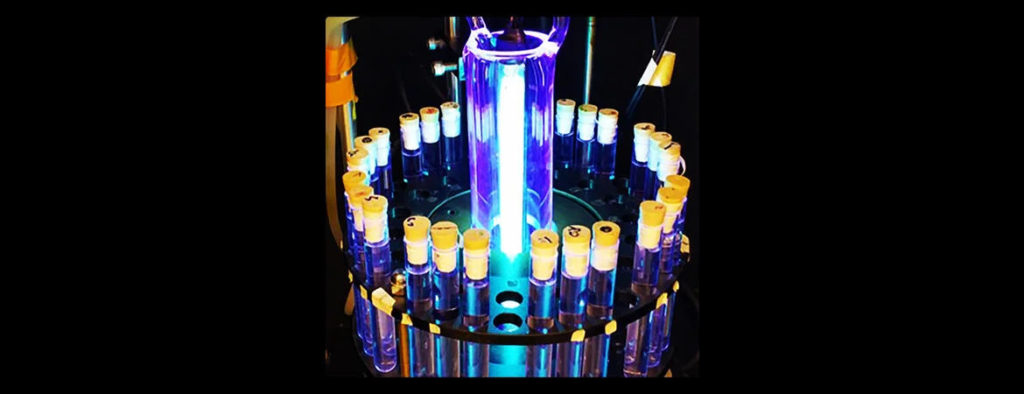

The patent-pending process infuses contaminated water with hydrogen, then blasts the water with high-energy, short-wavelength ultraviolet light. The hydrogen polarizes water molecules to make them more reactive, while the light catalyzes chemical reactions that destroy the pollutants, known as PFAS or poly- and per-fluoroalkyl substances.

This one-two punch breaks the strong fluorine-to-carbon chemicals bonds that make these pollutants so persistent and accumulative in the environment. In fact, the molecular destruction of PFAS increased from 10% to nearly 100% when compared to other ultraviolet water-treatment methods, while no other undesirable byproducts or impurities are generated, the UCR scientists reported in a paper recently published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters.

What’s more, the cleanup technology is green.

“After the interaction, hydrogen will become water. The advantage of this technology is that it is very sustainable,” said Haizhou Liu, an associate professor in UCR’s Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering and the corresponding author of the paper. The lead author of the paper, Gongde Chen, was a UCR project scientist who worked under Liu. Chen received his doctoral degree from UCR and now works as an engineer for the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board.

Liu’s laboratory developed the technology with help from a $400,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

PFAS are a family of thousands of chemical compounds characterized by fully fluorinated carbon atoms with stubbornly strong chemical bonds that last indefinitely in the environment – hence the moniker “forever chemicals.”

These compounds came into widespread use in thousands of consumer products starting in the 1940s because of their ability to resist heat, water, and lipids.

Examples of PFAS-containing products include grease-resistant paper wrappers and containers such as microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes, and candy wrappers; stain and water repellents used on carpets, upholstery, clothing, and other fabrics; cleaning products; non-stick cookware; and paints, varnishes, and sealants, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

Since these compounds persist and accumulate in the environment, dairy products and meat from animals exposed to PFAS are also sources of these compounds. In fact, PFAS are so ubiquitous, scientists have found them in the blood of nearly all people tested, according to a California legislative analysis.

Studies have linked exposure to certain levels of PFAS to many ill health effects, including increased risk for prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers, according to the EPA.

Exposure to these pollutants also may lead to decreased fertility or increased high blood pressure in pregnant women, developmental effects or delays in children, low birth weight, and accelerated puberty. PFAS compounds also have been found to compromise the immune system’s ability to fight infections and to interfere with hormone function.

Because of these health effects, federal and state officials are promulgating new cleanup standards for PFAS in drinking water and in groundwater below or emanating from toxic cleanup sites.

The EPA this fall took public comments on plans to designate two PFAS substances — perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid — as hazardous substances under the federal Superfund toxic site cleanup laws. If this regulation is approved, it would hold polluters accountable for cleaning up their contamination.

In California, the State Water Resources Control Board issued an order this year for public drinking water providers to test for PFAS. If the testing exceeds specified levels, the providers must issue public notifications, remove the source or sources, or treat or blend the water.

Given the regulatory push, Liu’s laboratory team is “marching toward commercialization” with help from a $50,000 proof-of-concept grant from UCR’s Office of Technology Partnership to scale up this technology to handle larger volumes of water, Liu said.

The technology involves emitting short-wavelength ultraviolet light into treatment tanks to excite water molecules.

“We are optimizing it by trying to make this technology versatile for a wide range of PFAS-contaminated source waters,” Liu said. “The technology has shown very promising results in the destruction of PFAS in both drinking water and different types of industrial wastewater.”