Original publication by Daniel Mercer for abc.net.au on 23 January 2023

(Supplied: APA)

The collapse of plans by two of Australia’s richest people to export solar power from the country’s sun-drenched north to Singapore highlights the extreme difficulty of developing mega renewable energy projects, according to experts.

Sun Cable, which is backed by iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest and tech billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes, was placed into voluntary administration last week amid a falling-out between the pair over the need to tip more money into the venture.

The failure has shone a light on the challenges facing ambitious green power export projects, which include the massive Asian Renewable Energy Hub proposal for the remote Pilbara region of Western Australia’s north-west.

David Leitch, a renewable energy analyst and former investment banker, said Sun Cable’s Australia-Asia Power Link project was technically feasible but its scale was unprecedented anywhere in the world.

Under the company’s existing plans, Sun Cable wants to build a giant 20-gigawatt solar farm in the Northern Territory before sending the power to Singapore via a 4,200km subsea cable through Indonesian waters.

(Reuters: Kevin Lam)

The farm, which would be backed by the world’s biggest network of batteries and cover an area equivalent to 12,000 rugby pitches, would supply up to 15 per cent of Singapore’s power needs.

Its estimated cost would be about $35 billion.

Revolutionary scale, not technology

Mr Leitch said the project appeared to be plausible, noting that the solar, battery and transmission technologies involved were mature.

However, he said the scale at which Sun Cable planned to deploy them was revolutionary and made development so much harder to achieve.

Crucially, he argued the subsea cable was likely to be its steepest hurdle, pointing out that it was more than five times longer than the world’s biggest, the 767-kilometre Viking link between the UK and Denmark currently under construction.

“It’s not the technical issues that worry me so much, but the fact it ties up a lot of the world’s cable manufacturing industry,” Mr Leitch said.

“The trouble with the cable manufacturer is he can see he’s got heaps of orders coming up from all over the place.

“He says ‘if you want to chew up all my capacity for two or three years, show me the dollars’.”

(Supplied: Diving Co)

Dylan McConnell, a senior research associate at the University of New South Wales, agreed that building a high-voltage electricity cable as long as the one planned by Sun Cable was likely to be the sticking point.

Dr McConnell contrasted the task in front of Sun Cable with plans for a second underwater cable between Tasmania and the Australian mainland, which were still in doubt despite being far more modest and technically achievable.

“You have a look at something like Marinus Link, which is a 250km cable, which is about 17 times shorter, it’s through the Bass Strait, which is about 50 metres to 60 metres depth, it’s within the same country,” Dr McConnell said.

“And it’s still got a bit of an uphill battle in front of it.”

Mega projects face ‘trade-offs’

According to Mr Leitch, who owns and runs analysis firm ITK Services, the difficulties faced by Sun Cable were emblematic of the challenges confronting mega renewable energy projects across the globe.

Mr Leitch said projects such as Sun Cable almost invariably had to overcome a “tyranny of distance” as many of the world’s sunniest and windiest places were far from major population centres.

He said this meant that while such projects could tap into the best renewable energy resources, they were also often handicapped by transport costs and logistical problems that could outweigh the benefits.

(Supplied: Sun Cable)

Similarly, grand plans to export solar power from north Africa to Europe via subsea interconnectors had languished for comparable reasons, he noted.

“You want to build as close to the market as you can,” he said.

“I mean, you’re trading off how cheap land is in the Northern Territory or in Western Australia versus how expensive it is to transport the stuff.

“That’s the trade-off.”

Central to the split between Mr Forrest and Mr Cannon-Brookes was Sun Cable’s plan to export the electricity via a subsea interconnector that runs from Darwin to Singapore in waters as deep as 2km in some places.

Through John Hartman, the chairman of his private energy company Squadron, Mr Forrest reiterated his support for a “game-changing solar and battery” project in the Northern Territory.

Billionaires go separate ways

However, Mr Hartman stressed that Sun Cable was “not commercially viable” in its current form and instead suggested the project would be better used to produce green hydrogen or ammonia.

Mr Forrest has outlined major plans to develop a green hydrogen business through Fortescue Future Industries.

For his part, Mr Cannon-Brookes is believed to be sticking by the plan for a subsea interconnector and has indirectly taken aim at Mr Forrest’s unwillingness to do likewise.

(AAP: Bianca De Marchi)

In the wake of Sun Cable’s demise, Mr Cannon-Brookes hit out at Mr Forrest, effectively accusing him of being the only shareholder who refused to take part in a $60 million fundraising required to keep the company afloat.

“We are confident Sun Cable will be an attractive investment proposition and remain at the forefront of Australia’s energy transition,” said a spokeswoman for Grok, Mr Cannon-Brookes’ private investment vehicle.

Despite Sun Cable’s setbacks, Mr Leitch suggested the project and others like it were well within the realms of possibility.

He pointed out that compared with turning renewable energy into products such as green steel or hydrogen and ammonia, delivering it as electricity along high voltage cables was relatively straightforward.

Mr Leitch noted China was already transporting huge volumes of green energy from its windy, sunny western provinces thousands of kilometres to its major population centres on the east coast courtesy of high voltage direct current power lines.

What’s more, he noted all major industries had to overcome technical and economic challenges before they could flourish.

Lessons in other breakthroughs

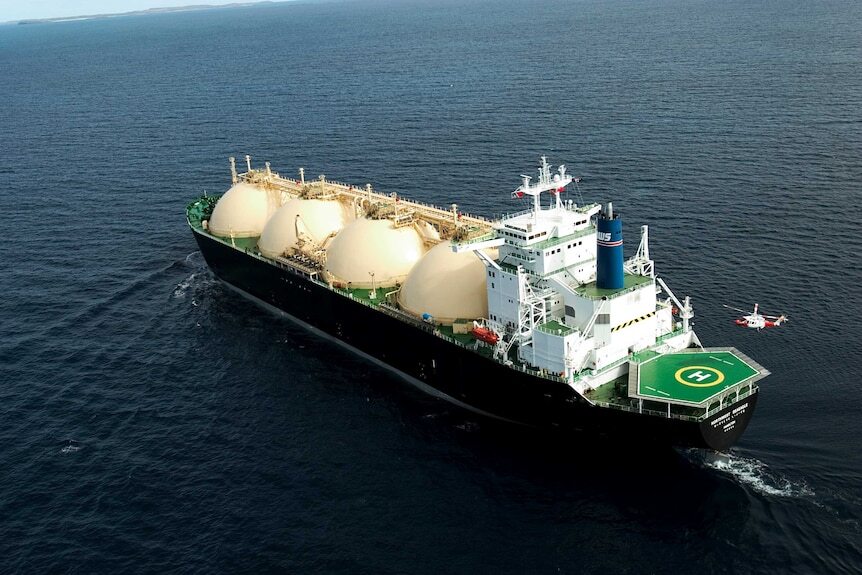

(Supplied: Woodside Energy)

To that end, he suggested Australia look no further than its massive liquefied natural gas industry, which was developed because of Japan’s desire to wean itself off oil from the Middle East 50 years ago.

“With these giant-scale renewable electricity projects, they are novel at the moment in their scale and no one has done one for export,” Mr Leitch said.

“To that extent, it has to be proved up by someone actually doing it and making it work.

“But that’s the history of technology.

“Someone had to build the first LNG tanker, too.”