Original publication by Ula Chrobak for knowablemagazine.org on 6 December 22

After long debate, economists and philosophers are reaching consensus on how to value future generations

CREDIT: ISTOCK.COM / MATEJMO

Barring a mass Homo sapiens extinction event from, say, nuclear war or another disaster, many more billions of humans will be born on the Earth in the coming millennia. For philosophers and economists, this poses a tricky question: What do we owe these future humans? How should we divide our resources between the 8 billion people alive now and those to come?

This isn’t just fodder for a thorny thought experiment. While it’s not often stated explicitly, all governments make trade-offs with the welfare of future generations when they make decisions that have long-term consequences, such as those related to energy production and infrastructure. Economists have even devised calculations to better explore such trade-offs, as well as a key variable — the social discount rate — which has been the subject of a hot debate for at least the past 15 years.

Just last month, the Biden Administration proposed a consequential change for how the United States handles the math used to probe this ethical question. Officials recommended that the government nearly quadruple its social cost of carbon — a monetary estimate of the costs to the economy, environment and human welfare for every ton of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere.

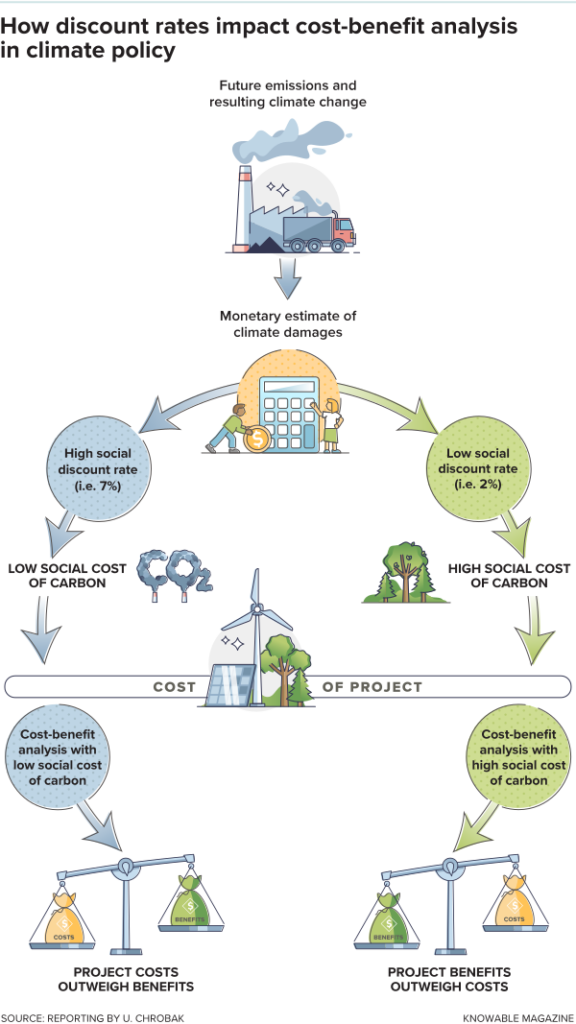

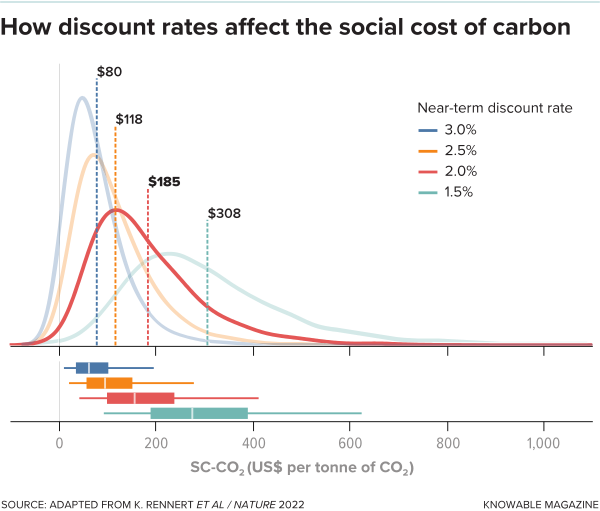

This value can be used to calculate, in dollars, the effect of various actions, such as the benefit of avoided carbon emissions from a new subway route or the costs of building natural gas lines. To reach this new estimate, officials used a new social discount rate: 2 percent, down from the 3 percent used previously (a larger discount rate translates into a lower cost). Because the resulting social cost of carbon is so much higher, this change makes it suddenly look far more costly to pollute — or to approve policies that would increase greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate policy wonks, many of whom wrote to the government to voice their opinions, closely watched this development because it could lead to a shift in how the US — the world’s greatest cumulative emitter of greenhouse gases — regulates its contribution of climate-heating gases. But the US is just one of many entities using social discount rates to estimate how much it’s worth, in today’s dollars, to avoid billions in climate damage in future decades.

Across influential institutions around the world — including governments as well as financial organizations such as the World Bank — economists punch social discount rates into mathematical formulas to weigh the future costs and benefits of proposals to build new bridges and roads, invest in clean energy research and regulate greenhouse gases. You’re probably already familiar with the results of these analyses, even if you didn’t know about social discount rates. Consider when a politician says that a proposed environmental regulation would cause too much harm to the economy, for example. How do officials make those calls? The secret ingredient is social discount rates.

“It is probably the single most important variable in terms of working out what you have to do for climate change mitigation,” says Mark Freeman, an economist focused on intergenerational finance at the University of York and coauthor of a recent review of social discounting in the Annual Review of Resource Economics. He concludes this based on current research that found that the social cost of carbon is more sensitive to policymakers’ choice of discount rate than other variables. “People need to worry about this more. It matters.”

CREDIT: RESOURCES FOR THE FUTURE

Seemingly small changes in discount rates can result in vastly different climate policy outcomes. During the Trump administration, officials claimed that a rollback in automobile fuel efficiency standards would result in $6.4 billion in economic benefits. They based their calculations on a discount rate of 7 percent, which “basically means you don’t care about anything that happens after about 25 years,” says Ben Groom, an economist at the University of Exeter and lead author of the Annual Review of Resource Economics paper. Under President Barack Obama, those same fuel efficiency standards had been deemed to produce a net economic benefit based on a 3 percent discount rate.

Economists use discounting to weigh the pros and cons of getting things sooner rather than later. For individuals, such calculations can be pretty straightforward: “If I were to offer you a Lamborghini today or a Lamborghini in 10 years, who’s going to wait for 10 years?” Freeman sometimes asks his students. Our preference for getting that Lambo today — or an equivalent sum of cash, if you don’t care for sports cars — isn’t just impatience. It’s rational, in economic terms. A hundred dollars is, generally, going to be worth more if you get it today rather than in a year. That’s due to factors like inflation, as well as the lost opportunity to invest your Benjamin today and watch it grow with compound interest.

When economists consider the impacts of an investment today on the welfare of large groups of people, the discount rate becomes a social discount rate — and weighing the factors that influence the rate gets more complicated. One reason is that policymakers can’t snap their fingers and pour money into every public need at once. Instead, they have to assess the most cost-effective use of funds by adding up all the costs of a program or policy, then adding up all the benefits, and comparing the two price tags.

These comparisons are relatively easy when considering a project with immediate results, such as an investment in schools or safe drinking water. But sometimes officials have to compare near-term priorities with projects that may not fully pay off for 100 or more years, as is the case with many climate policies. It’s not always selfishness that might prevent policymakers from acting on climate change, says Tamma Carleton, an economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “They are also trying to think about our educational systems, poverty eradication and healthcare.”

Economists use social discount rates to determine how much a future benefit, like $1 trillion in averted climate damages in 2100, would be worth today, explains Carleton. In the US, federal agencies are required to prepare cost-benefit analyses for projects that could have a large economic impact now or in the future. If the benefits far outweigh the costs, a proposed rule or bill is more likely to be seen as viable and move forward.

But here you might say, is it really necessary to discount future people in order to do these comparisons?

Welcome to one of the most consequential yet obscure ethical debates known to humankind. About 15 years ago, Nicholas Stern, a climate economist at the London School of Economics, set off an argument about discounting that continues today. In the 2006 UK government study led by Stern, The Economics of Change: The Stern Review, he used a social discounting approach that explicitly took our ethical responsibility to future generations into account.

Stern used a very low discount rate, 1.4 percent, to support the conclusion that large investments were urgently needed to prevent future climate damages. That value — while still discounting a small amount for future economic growth and the possibility of human extinction — treated the welfare of future generations equally. As he and coauthors summed up, “if a future generation will be present, we suppose that it has the same claim on our ethical attention as the current one.”

However, future economic growth is not 100 percent guaranteed, and the damage wrought by climate change could worsen life for individuals in the next century. In this scenario, some economists have argued, using a zero or even a negative discount rate would make the most sense.

These arguments have irked some economists, including William Nordhaus of Yale University, who was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2018 for his work in climate change economics. “The Review takes the lofty vantage point of the world social planner, perhaps stoking the dying embers of the British Empire, in determining the way the world should combat the dangers of global warming,” he wrote in a paper published in the Journal of Economic Literature. Nordhaus thought that Stern’s approach risked impoverishing people today to tackle future climate change, and favored a higher discount rate based on market interest and savings rates.

Today, most economists favor some amount of discounting, for two reasons: People tend to be impatient, and future people will be richer than today’s. This desire for more immediate payoff isn’t necessarily a bad thing, says Freeman. Most of us already discount future people, he points out. “I mean, I love my children more than I love my great-, great-, great-grandchildren,” he says. “So why should I not value my children more than my great-, great-, great-grandchildren?”

While it may seem intuitive to say future people deserve the same consideration as people today, many economists counter that the people of the future will probably be richer as a result of economic growth. And the same sum of money is less meaningful for a rich person compared to a poor person. “One hundred dollars matters more for me than it does for Jeff Bezos,” says Carleton. Adds Groom: “If the future is richer, then we are the poor people.” Groom and others argue that putting money toward future people without discounting is like taking money from the poor to give to the rich.

Some experts — including economists and philosophers focused on intergenerational ethics — add that we need to consider the possibility that the human species will go extinct. It would be a shame, they say, to go all in on programs benefiting humans hundreds of years from now, only for them to end up dying out due to a meteorite or nuclear war.

Increasingly, governments are using lower discount rates to reflect the urgent need to address climate-warming emissions. The recent US Environmental Protection Agency report used a 2 percent discount rate as one factor in recalculating the social cost of a ton of carbon, down from the 3 percent rate used by the Obama administration. The adjustment contributed to an increase to $190 from $51 per ton. Earlier, at the end of 2020, New York State officials updated their own social cost of carbon to $125 a ton, also by using a discount rate of 2 percent. The change affects many government decisions, explains Maureen Leddy, director of the state’s office of climate change. For example, an agency purchasing new vehicles for its fleet has to factor in the social cost of carbon emissions generated by buying gas-powered cars, which could make electric vehicles look much less expensive in comparison.

CREDIT: ORJAN ELLINGVAG / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

But why is 2 percent so hot these days? One reason is that the rate seems to bridge the ethics-versus-pure-economics divide. In survey research, Freeman and Groom found that the median discount rate chosen by both economists and philosophers was 2 percent, which in turn supports policy actions that are expected to limit global warming to 1.5°C by 2100. The two groups don’t necessarily get to that number the same way, but they seem to agree that rate is best for discounting long-term government projects, such as those that would affect climate change.

That said, it might not be fair to use the same low social discount rates worldwide. A low discount rate might motivate climate action in richer countries, but shouldn’t necessarily be used in less developed countries, explains Nfamara Dampha, a researcher of natural capital and ecosystem services at the University of Minnesota and an author of a review on discounting and environmental change in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources. “The problem with [using] the same approach in developing countries is that there is already a lot of poverty, there is already a lot of inequality,” he says. By using a low discount rate, “you’re constraining those people to minimize their consumption for the benefit of the future.”

For countries with acute problems such as a lack of clean water, higher discount rates may be warranted to direct public funds toward the immediate benefits of alleviating such issues. Meanwhile, Dampha says that wealthier countries that have contributed a large share of climate-warming emissions should use low discount rates when funding environmental projects in developing countries, as a matter of climate justice. “The payments for ecosystem services should be sourced globally to developing countries,” he says.

In the future, Freeman hopes that the public can be more involved in discussions involving social discount rates. “At the moment, it’s all very behind closed doors, which isn’t great,” he says. “Why should I have any special say in what the discount rate is?” At their core, after all, these social discount rates are political decisions — ones that can directly impact policies, including how to temper the worst effects of climate change.