Original publication by Loz Blain for newatlas.com on 21 November 22

This remarkable desalination device, made from 170,000 recycled plastic bottles, runs on mechanical power from waves as it floats in the ocean, and creates up to 13,000 gallons (53,000 liters) of fresh water a day – while discharging far less concentrated salty brine than other designs.

Only 3% of the Earth’s water is fresh water – take away the water locked up in icy glaciers and you’re looking at just 1%. So humanity finds itself on the wettest planet in the solar system, surrounded by water, and yet still facing critical fresh water shortages that are already affecting about half the global population.

As the effects of climate change continue to unfold, and the global population rises toward a projected peak around eleven billion by the end of this century, water scarcity is going to get a lot worse, and desalination technology will become more and more critical and ubiquitous.

Scaling up current desalination methods poses some serious problems. Firstly, it will require enormous amounts of energy as it scales up – and this comes during the difficult transition from dirty to clean energy, when power will be at a premium. Secondly, land-based industrial desalination plants take in enormous quantities of salt water, then remove most of the water and pump a highly-concentrated salty brine back into the ocean, often contaminated with chemicals used to pre-treat the water and keep the equipment clean. This heavy, salty discharge tends to sink to the sea floor, where it can cause ecological damage.

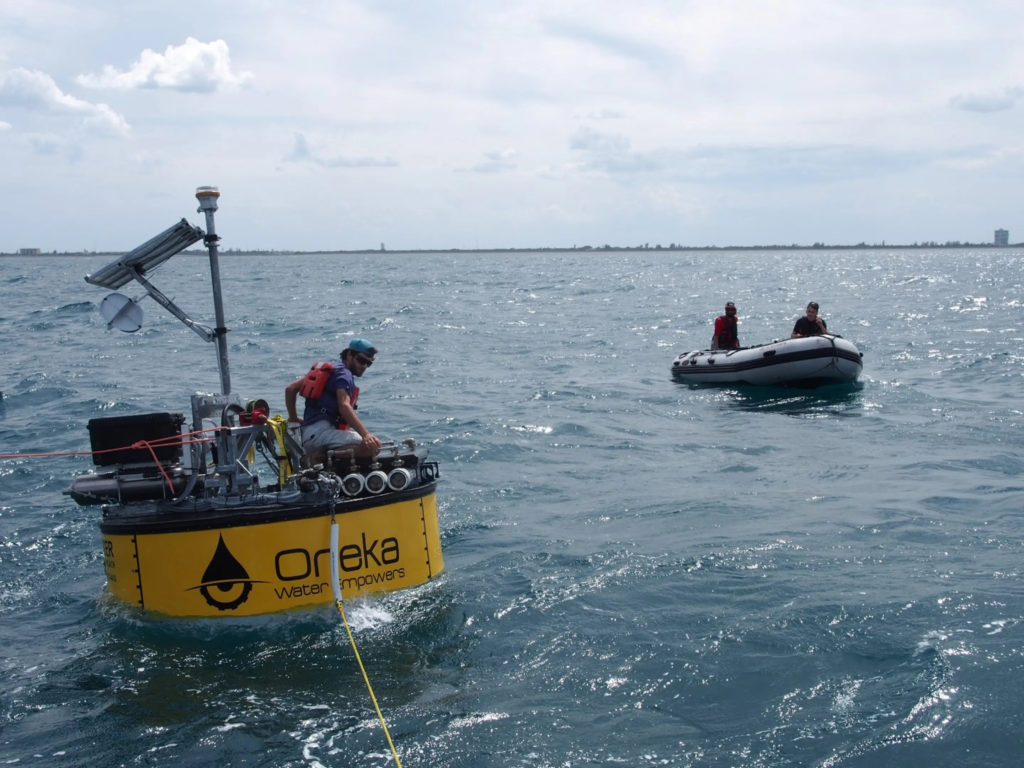

But there’s no way around it; humanity will need more and more desalination facilities going forward. And that’s why Oneka’s wave-powered floating desalination buoys may prove to be such a valuable development.

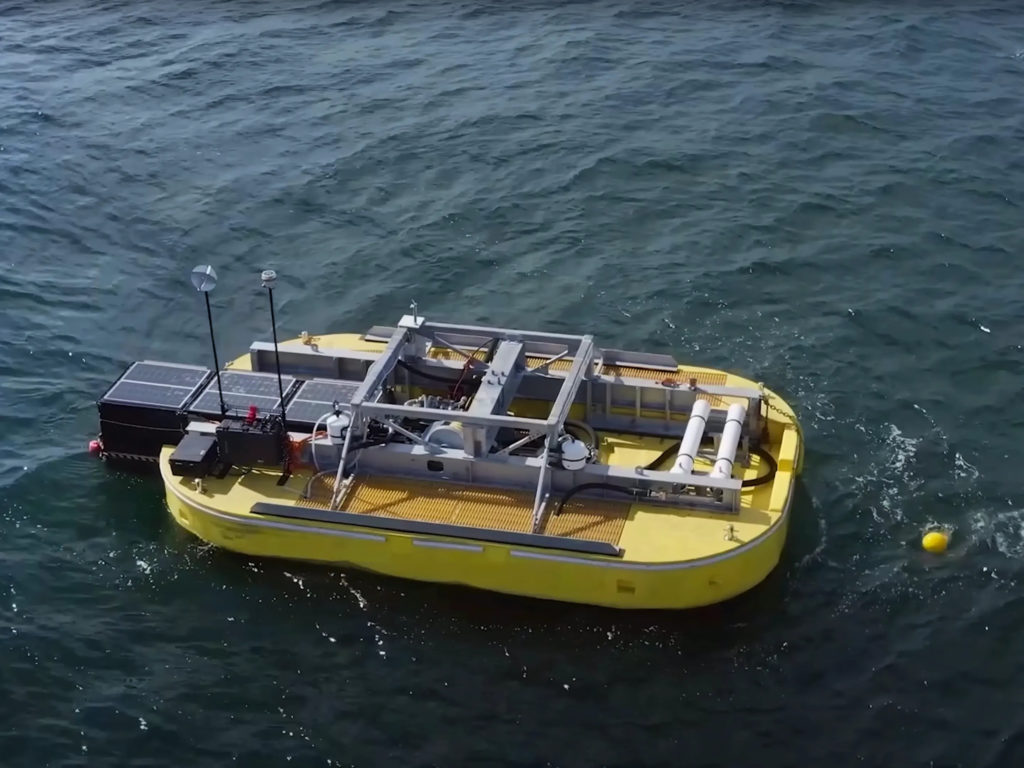

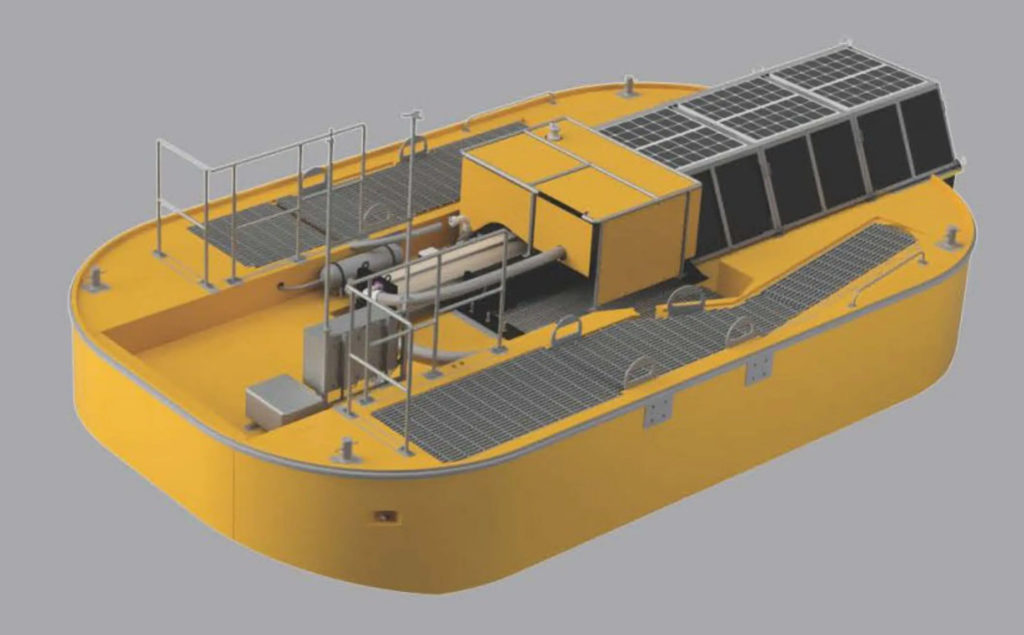

Oneka has designed these things from the ground up to be eco-friendly. For starters, they’re built mainly from recycled plastic bottles; each “Iceberg” class buoy represents more than 170,000 bottles that’ll no longer go to landfill or join their people in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

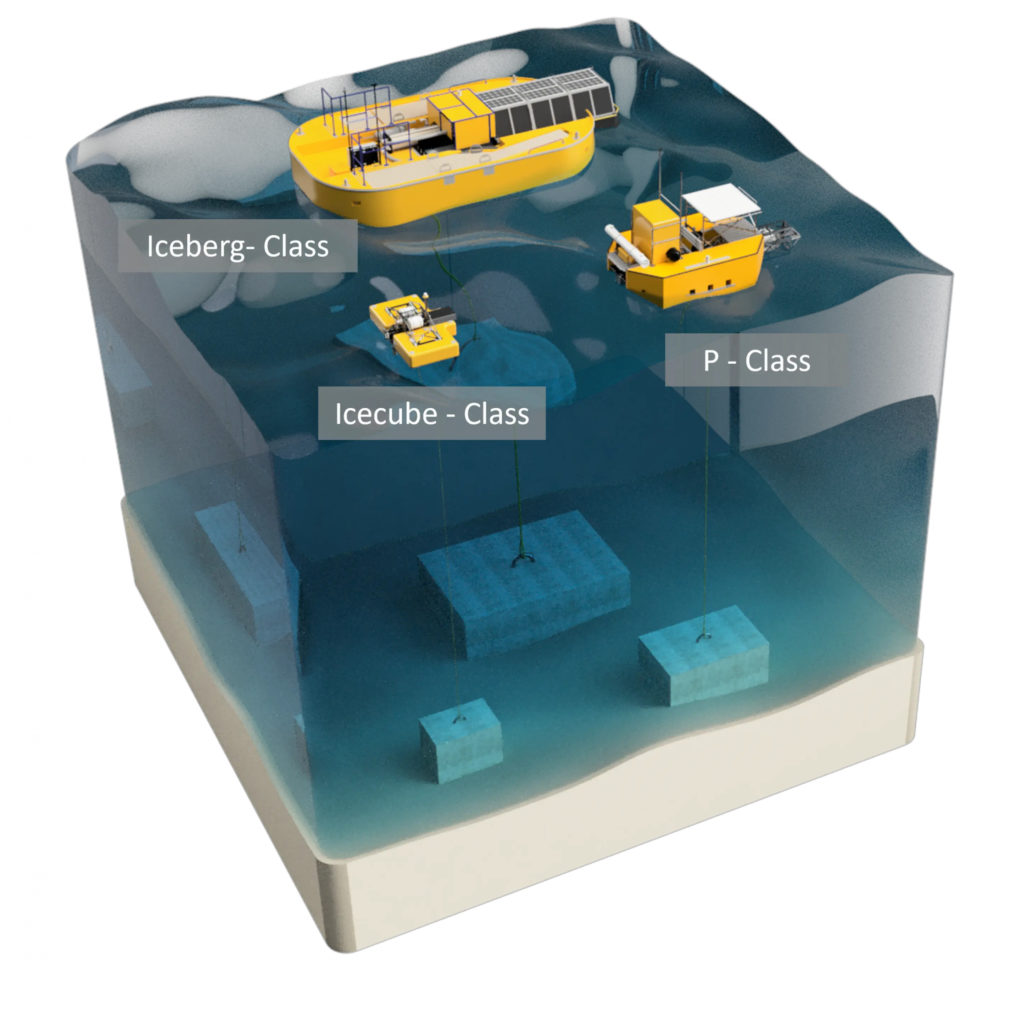

They operate entirely on wave power. Anchored to the sea floor anywhere with an average wave height of more than 1 m (~3 ft), they absorb energy from passing waves, and convert it into mechanical pumping forces that draw in seawater and push around a quarter of it through a reverse-osmosis desalination system to create fresh, drinkable water, which is pumped back to land through high-density polyethylene pipelines, again using only the power provided by the waves.

The remaining three quarters is mixed back in with the briny discharge from the desalination process and released back into the sea. It’s only 30% saltier than the water around it, a negligible change compared with the much more concentrated brine released by land-based desalination plants, and since these buoys are typically anchored at least a mile (1.6 km) out to sea, in large arrays with lots of spacing between units, the brine disperses well and toxic ecological effects are minimized. Oneka claims its own testing has found that within about 10 feet (3 m) of each device, there’s already no measurable increase in water salinity over the baseline.

To minimize the possibility of sucking in fish, eggs or other small aquatic wildlife that probably wouldn’t appreciate being desalinated, fine mesh filters protect the water intakes, and the pumping cycle includes backwashing. Oneka claims “there is no danger to fish, eggs or plants.”

Iceberg-class units are designed to generate between 30-50 cubic meters (8,000-13,000 gallons) of water per day – enough for the daily needs of between 100-1,500 people, depending on lifestyle and consumption. Onboard sensors, powered by small solar panels, continuously test the water that’s produced, ensuring it meets relevant standards. Oneka offers some post-processing to adjust the taste of the water, or to tune it to the advantage of agricultural users.

They do require some maintenance – between three to seven visits per year to each unit for preventative and general maintenance. But with this taken care of, each unit is designed to last between 15-20 years of service.

Clearly, the output of these relatively small machines is nowhere near that of the biggest land-based desalination plants. Indeed, you’d need more than 20,000 iceberg-class buoys operating at maximum capacity to match the clean water output of the world’s biggest desalination facility, the Ras Al-Khair Power and Desalination Plant in Saudi Arabia.

Oneka says it’s working on “utility-scale devices,” which could move the needle further in areas that need larger quantities. These “Glacier Class” machines, according to Just Have a Think, will produce about 10 times as much as the Icebergs, and according to Saltwire, they’ll become available in 2023 and begin demonstration trials off the coast of Barrington, a community of 4,000 people in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Still, where they match local requirements, the existing machines appear to offer an economical, scalable and reliable way to generate clean water with no carbon dioxide emissions, no requirement for coastal land space, no drain on the power grid, and a carefully limited effect on ocean ecology. It’s an impressive technology, and we can think of few better ways to re-use a couple hundred thousand old plastic bottles.

Source: Oneka via Just Have a Think