Original publication by Melissa Hobson for theguardian.com on 14 March 2023

Photograph: Melissa Hobson

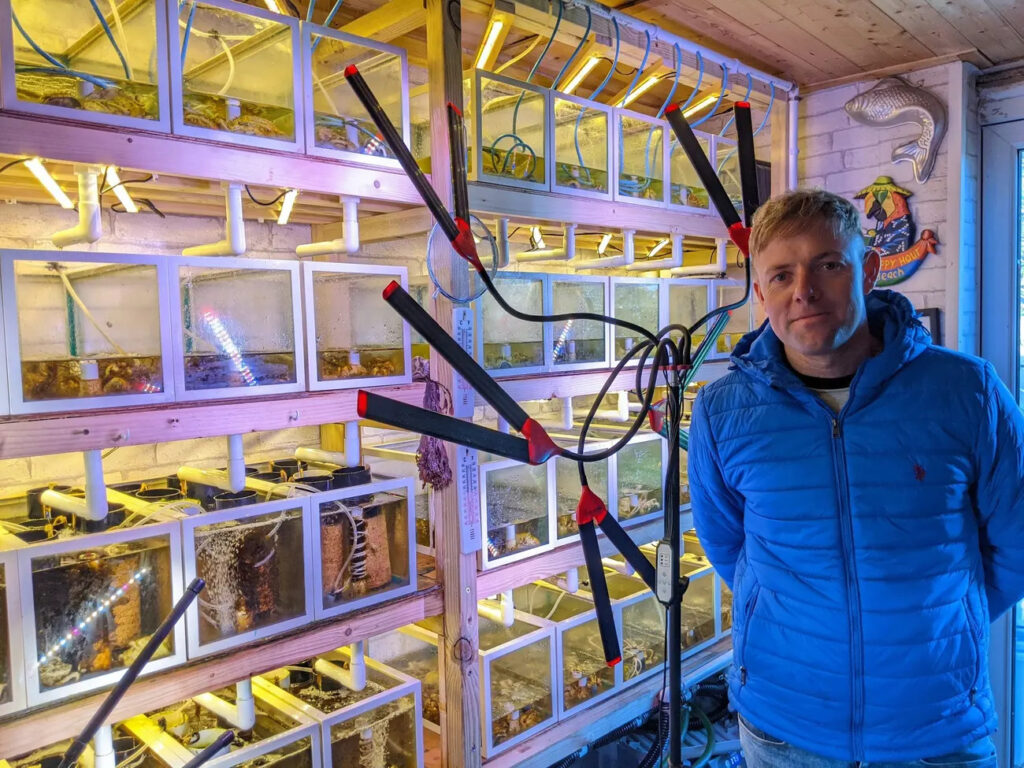

Steve Allnutt has watched the lush beds disappear from local waters over the years, and decided to take on the job of restoration himself

Steve Allnutt shivers and zips up his coat as he checks on the water tanks holding thousands of specimens. He confirms the temperature, adjusts the lighting and fishes out a tiny piece of kelp to inspect under his microscope.

Allnutt’s unusual setup – in his garage in Lancing, West Sussex – features 20-odd tanks full of the algae. He aims for the atmosphere to mimic natural ocean conditions, so the air in the garage is brisk but the light is cool and calm, like a winter’s day. In summer, he’ll need to wear sunglasses.

A 40-year-old NHS worker, Allnutt has made it his mission, around his busy work schedule, to rewild 3 hectares (7.4 acres) of kelp beds in Sussex.

Kelp is vital for the health of the ocean: it grows in “forests” that are a huge nursery for migrating marine life, provides critical habitats for young marine species and acts as an important carbon sink.

As an avid freediver since the age of 12, Allnutt remembers how his local coastline once was – full of lush kelp beds that brimmed with marine life. He used to dive near Hove in an area with kelp so dense that “you’d hardly see the rocks and mussel beds” beneath it.

Now, he says, “it’s just disappeared”.

Most of the UK’s kelp beds have been wiped out by destructive fishing practices such as bottom trawling that leave the seabeds scarred and barren. “We’ve taken so much out of the sea but we’ve not put anything back,” says Allnutt.

What kelp remains, he noticed, is resilient, and he began to wonder if a restoration project could simply “reboot the whole system”. When a new law in 2021 banned trawling in 200 square kilometres of Sussex’s inshore waters, Allnutt was initially excited – but soon he realised that, although the areas were newly protected, the government had no actual restoration plans. If no one else would act, he figured, it was down to him.

Photograph: Steve Allnutt

He set up the tanks in his garage and planted them with kelp tissue he collected from freediving. To cover the cost of the equipment, he picked up extra shifts at the hospital where he works as a physical therapy technician with patients who have had knee and hip replacements. Later, he launched a crowdfunding scheme – called the Sussex Seabed Restoration Project – which has raised more than £3,000. Local restaurants even donated oyster shells for the kelp to grow on.

Juggling the project around his busy hospital schedule often sees him mixing up kelp “sporophytes” while having breakfast. But, although he studied marine science, Allnutt had a lot to learn about breeding algae. Scientists from around the world who heard about his project got in touch with advice on how to encourage the kelp to reproduce, but for months there was little progress. At last, one day, he looked through the microscope to see “a whole hornet’s nest of spores” whizzing around.

“One bottom trawl across a restored area could wreck days, weeks or months of hard work

-Hugo Tagholm,

Oceania Uk

Allnutt’s next step will be to plant the kelp, with several possible methods, all of them using natural or biodegradable materials. The “green gravel” approach involves growing kelp on small stones and sowing these into tiny crevices on the seabed. Allnutt has also created 900ft of biodegradable “kelp lines” that can be wrapped around the substrate to encourage the plants to attach themselves while the lines dissolve.

He will also place oyster shells with kelp growth already established on them straight on to the seabed. Each location will be tagged using GPS to help him monitor growth.

Photograph: Steve Allnutt

“I’m delighted to see this zeitgeist of restoration and optimism coming back,” says Hugo Tagholm, the executive director of the marine conservation NGO Oceana UK. The organisation supports projects that aim to rewild “blue carbon” habitats, he says, while noting that they don’t work in isolation. Harmful industrial practices such as overfishing, trawling and the sewage being pumped into our rivers and seas can destroy restoration efforts “in one fell swoop”, he says.

“One bottom trawl across a restored area could wreck days, weeks or months of hard work. We’ve got to tackle industrial pressures as well as restoring the habitat so we can see marine life bounce back.”

While bottom trawling is now banned in Allnutt’s local area, other types of fishing such as gill nets, trammel nets and lobster pots are still allowed. But Allnutt says he has widespread community support, and hasn’t had any complaints from local fishers. As he sees it, creating a healthier marine ecosystem will help them, too.

He considers government regulation more of an obstacle. Marine laws that forbid dropping objects from a floating vessel mean he can restore kelp only while freediving from the beach. This restricts his activities to the summer, when conditions are better for freediving, but it is in winter that the nutrient-rich waters are best suited for kelp to grow. “It’s really hard [to make progress] against the red tape,” he says.

Back in his garage, the growth rate of the kelp continues to astound him. “Plants are just growing in the water not attached to anything,” he says, to the extent that some days while freediving he just dumps buckets of these extra spores straight into the water.

After he has planted his 3 hectares of kelp, positioned 15 to 20ft apart, Allnutt hopes next to secure a permit to dispatch kelp from a boat – and funding for that boat so that he can run the project year-round.

“I’m determined to do it”, he says, “but I can’t do it on £3,000.”